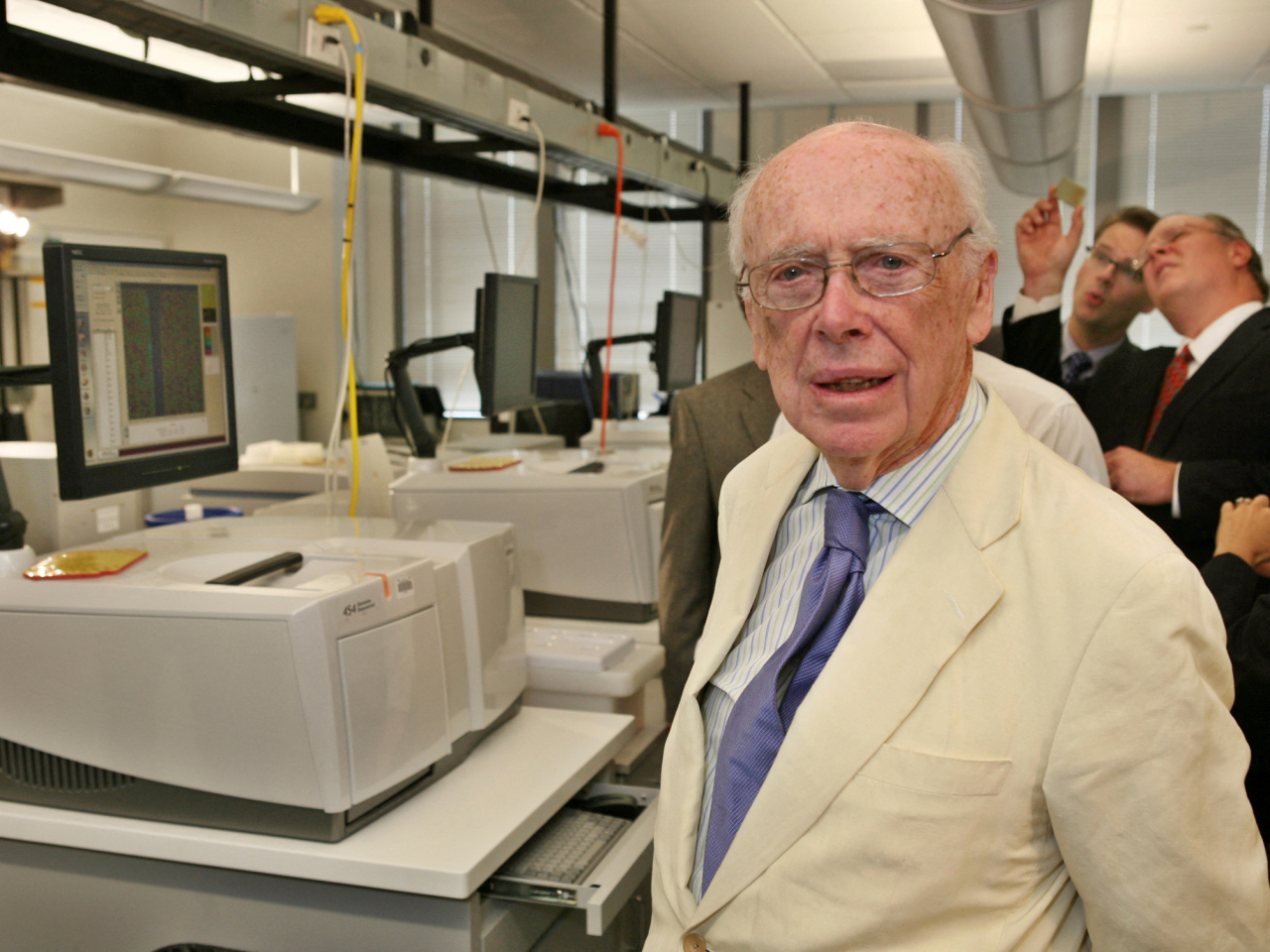

James D. Watson, whose co-discovery of the twisted-ladder structure of DNA in 1953 helped light the long fuse on a revolution in medicine, crime fighting, genealogy and ethics, has died. He was 97.

The breakthrough - made when the brash, Chicago-born Watson was just 24 - turned him into a hallowed figure in the world of science for decades.

Watson shared a 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for discovering that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other to create what resembles a long, gently twisting ladder.

That realisation was a breakthrough. It instantly suggested how hereditary information is stored and how cells duplicate their DNA when they divide. The duplication begins with the two strands of DNA pulling apart like a zipper.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix would become an instantly recognised symbol of science, showing up in such places as the work of Salvador Dali and a British postage stamp.

The discovery helped open the door to more recent developments such as tinkering with the genetic make-up of living things, treating disease by inserting genes into patients, identifying human remains and criminal suspects from DNA samples and tracing family trees . But it has also raised a host of ethical questions, such as whether we should be altering the body’s blueprint for cosmetic reasons or in a way that is transmitted to a person’s offspring.

Watson never made another lab finding that big. But in the decades that followed, he wrote influential textbooks and a best-selling memoir and helped guide the project to map the human genome. He picked out bright young scientists and helped them. And he used his prestige and contacts to influence science policy.

Watson died in hospice care after a brief illness, his son said Friday. His former research lab confirmed he passed away a day earlier. Both of Watson’s Nobel co-winners, Crick and Wilkins, died in 2004. (AP)